When it comes to maintaining healthy white-tailed deer populations, state agencies have few tools in their arsenal for dealing with afflictions like chronic wasting disease and epizootic hemorrhagic disease. Even though each of these diseases have been studied for over 50 years, state wildlife agencies have been stymied – unable to develop any effective vaccines. Even if a vaccine could be developed, how could state officials effectively deliver it to free-ranging whitetails?

Michigan is the first state in the country tackling the vaccine delivery question. For nearly 50 years, deer hunters and cattle farmers in the Great Lakes State have been plagued by bovine tuberculosis, or bTB, a pernicious disease that not only kills deer but has repeatedly threatened the worldwide beef industry. Using a TB vaccine originally developed for humans, researchers are testing the efficacy of delivering an oral vaccine to wild deer in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, where bTB is annually found. What they learn just may hold the keys to better managing not only bTB, but other deer diseases impacting whitetails. Before digging into their work, let’s briefly look at what bTB is, its history in the U.S. and how it’s impacted deer AND humans. Then we’ll delve into the Michigan study to see whether it may finally offer wildlife managers some answers for combatting bovine TB but other diseases threatening deer nationally.

What is it?

Bovine tuberculosis is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis). First identified by Theobald Smith in 1898, bTB has been around for millennia. Archaeologists have discovered TB DNA in the bones of ancient bison inhabiting what’s now Wyoming more than 17,000 years ago. Symptoms of bTB in deer include coughing, nasal discharge, difficulty breathing and weight loss. Whitetails can have bTB for years and not show symptoms – or even never show symptoms.

Any mammal, including humans, can get bTB. The disease is similar to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the TB strain humans usually contract. In 1900, TB was the leading cause of human deaths in the U.S., with about 10% infected with bTB from exposure to sick cattle. Today, more than 200 humans in the U.S. are diagnosed with bTB each year. Bison, deer and elk are the usual culprits transmitting it to domestic bovine in the U.S. and Canada.

In 1933, New York was the first state to identify bTB in white-tailed deer. Since then, it’s been found in many states and many deer species, including Hawaii (axis deer), Minnesota (whitetails) and Montana (mule deer). Michigan first identified bTB in 1975 in a 9-year-old white-tailed doe taken by a hunter in Alcona County. Since then, Michigan is the only state in the nation where bTB is annually found among wild deer.

Michigan’s management of bTB

After 1975, Michigan would go nearly two decades before identifying another bTB-positive deer. In 1994, bTB reared its ugly head again – this time in a 4-year-old buck taken by a hunter in Alpena County. Since then, bTB has been discovered in wild deer in 16 counties. Cases are concentrated in Deer Management Unit 487, comprised of Alcona, Alpena, Iosco, Montmorency, Oscoda and Presque Isle counties. To date, 1,020 white-tailed deer have tested positive for bTB. In the TB core area of DMU 452, comprised of portions of Alcona, Alpena, Montmorency and Oscoda counties, the bTB prevalence rate among whitetails has remained at about 2% over the last decade.

“Bovine TB is a density-dependent disease, meaning it is more readily transmitted in areas where deer densities are high, where it can then become self-sustaining,” explained Emily Sewell, a wildlife health specialist for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

For decades, the DNR and the Michigan Department Agriculture and Rural Development have collaborated to try to eradicate the disease. Strategies focus on DMU 487 and include providing high antlerless deer harvest opportunity quotas, reducing license/tag fees, banning baiting/feeding, offering free disease control permits to cattle producers, and increasing the biosecurity of farms to prevent deer from accessing cattle feed and sharing resources with domestic cattle.

Michigan officials believe the bTB landscape could worsen, prompting a need for other management strategies.

“Modeling [statistical] and trends in declining hunter numbers suggest that the tools we have been using to manage the disease may not be enough to keep it at its current prevalence level,” Sewell added. “So we need additional tools to reduce and ultimately eliminate TB from Michigan’s deer herds.”

The trial

The bTB vaccine study in Michigan is the culmination of decades of research and collaboration among many state and federal agencies. Phase one began in 2005 with researchers using all they had learned about bTB-positive deer to model how best to deliver an oral vaccine to free-ranging whitetails. Phase two began in 2021, when an oral vaccine was tested on captive deer at National Wildlife Research Center in Fort Collins, Colorado. There, scientists worked out how best to deliver an oral vaccine, how much vaccine is needed and other particulars to ensure deer will voluntarily consume the vaccine delivery unit, or VDU.

It’s important to note what the vaccine does AND doesn’t do.

“The vaccine doesn’t prevent a deer from contracting TB, but instead provides a greater degree of protection compared to deer that aren’t vaccinated,” said Dr. Kurt VerCauteren, a supervisory research wildlife biologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “Transmission of the disease is substantially less for vaccinated deer, and if they have TB, the vaccine reduces the likelihood of a deer progressing to stages of severe infection.”

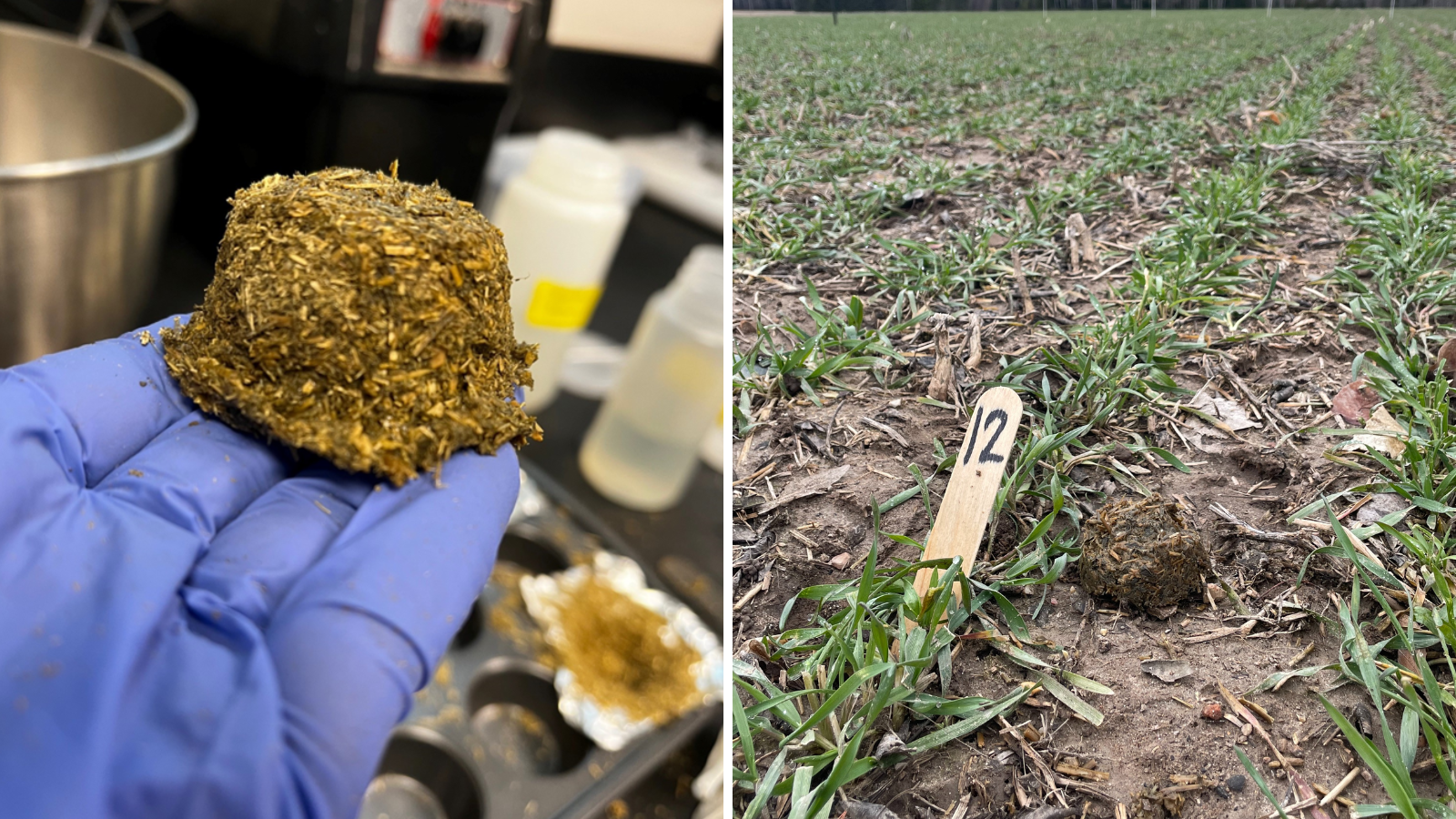

The VDU consists of a 1-cubic centimeter liquid vaccine protected by an alginate sphere inside a 2-inch cube of alfalfa, molasses and gluten (for binding). If you’ve ever seen water in edible pods provided to marathon runners in England, you get the idea of what the oral vaccine resembles. A deer picks up and bites into the VDU, bursting the alginate sphere, which then coats its mouth and throat with the vaccine. Only one VDU is needed for vaccination and provides about four months of protection to deer.

After securing landowner permission, phase three of the study involved testing the efficacy of delivering the oral vaccine to wild deer. From February to March of 2024, researchers first acclimated deer to the edibles by placing placebo VDUs (no vaccine) at 16 sites in Alpena County. They then deployed 100 VDUs to each of the sites and monitored them with game cameras. After two days, officials returned and collected any uneaten VDUs.

“The average uptake was 58% among all of the sites, which exceeded our expectations,” explained Sewell. “Some sites had 100% uptake, and deer visiting the sites ranged from three to 20.”

The last phase will involve USDA sharpshooters harvesting up to 10 deer at some of the trial sites to study immune responses to the vaccine and/or exposure to bTB from contact with TB-positive deer. Researchers will also review game camera photos/videos to learn more about how deer responded to the VDUs to improve future studies.

Funding for the study comes primarily from Michigan hunting license sales. Both the current study and prior research that led to it have been expensive and time-consuming, prompting some to question whether it’s worth it to try to reduce a disease that impacts only about 2% of whitetails in one small Michigan region. VerCauteren responds by pointing to the harmful impact bTB can have on more than deer and deer hunters.

“That small population of TB-positive deer in that little part of one state out of 50 puts our entire international livestock trade at risk,” he said. “If Japan or China wanted an excuse to no longer accept American beef, they’d have it because of bovine TB in some of our deer. It’s also very hard for agricultural officials to have to show up and tell a farmer that his best breeding cows have to die because they have TB.”