As if to prove whitetail lore and legend are endlessly fascinating, one of hunting’s historic tales took an unexpected turn in 2025. The story, now 68 years old, began in 1958 near the small, central Nebraska town of Sargent. A salt-of-the-earth rancher named Ben Barnhart saw three giant bucks. The following spring, he was tending to a newborn calf when he spotted a massive shed antler from one of the three bucks, hanging in a willow bush.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this story …

After making sure his calf had what it needed to survive, a quick search turned up the matching antler. Barnhart took them back to his barn and dropped them in a corner on the dirt floor, not knowing that he, his ranch, and this pair of antlers were destined for a central spot in the annals of America’s favorite game animal. It wasn’t until 1996 that these antlers became known as “The General,” and in 1998 they were recognized by the North American Shed Hunters Club (NASHC) as the biggest typical antlers a wild buck has ever worn. Up to that time, Barnhart’s discovery of the antlers remained a simple tale told to a few locals. Ben is gone now, but as stories often do, this one has become complicated.

Hard to Believe

Starting with their sheer size, so much about these antlers is hard to believe. Among the millions upon millions of white-tailed deer harvested in North America, only a few typical bucks have had an antler that scores 100 inches. A tape measure proves that The General carried 100 inches of typical antler on both sides of his head, and it is the only wild whitetail buck ever to do that.

Some people have doubted that three bucks of massive size would be running together, but 1958 was the first year Nebraska had a firearms deer season in central Nebraska (Zone 7), only a four-day season. Fertile soil offering plenty of nutrition and zero hunting pressure means it’s entirely possible that a bachelor group of three could all reach a monster level of maturity.

It’s also hard to believe that anyone would find the buck’s cast antlers, because few people in that era had much interest in shed antlers. Chalk it up to synchronicity — it so happened that a cow giving birth to a calf put Barnhart in the right place at the right time. For almost seven decades now, people have wondered how long this buck lived. In 2025, it was proven that The General went on to live several years longer.

And, from the instant information perspective we have in 2026, it’s hard to believe that the biggest whitetail antlers in the world could remain hidden for 36 years, but that’s what happened. In 1959, they were just a big set of antlers. In the mid-1970s, Barnhart’s son had them mounted to a board and hung them on a wall in the farmhouse where family members and a few neighbors could appreciate them. Still, they remained out of the public eye until 1995.

Didn’t anyone report the antlers to a scoring authority? No, because in those days antler collectors were rare if they existed at all, and Barnhart certainly wasn’t one of them. It was just pair of antlers, very big ones, but no one gave much thought to how they measured up to other big antlers. Few people knew what it meant to score an antler anyway. The Boone & Crockett system of scoring had been adopted only nine years earlier, so antler scores weren’t on many people’s minds. And no organization kept records of shed antlers at the time.

The shed antlers prove that The General survived that first central Nebraska hunting season in 1958, but imagine if a hunter had killed it during that four-day season and entered it into the Boone and Crockett record book at any time within the 20 years that followed. Much of deer hunting history would have changed. Wisconsin’s Jordan Buck (killed in 1914 but not declared the record until 1978) would have had a short reign, or maybe no reign at all. While we probably would have heard of Saskatchewan’s astonishing Milo Hanson buck (1993), it would never have been the world record.

Good News, Then Very Bad News

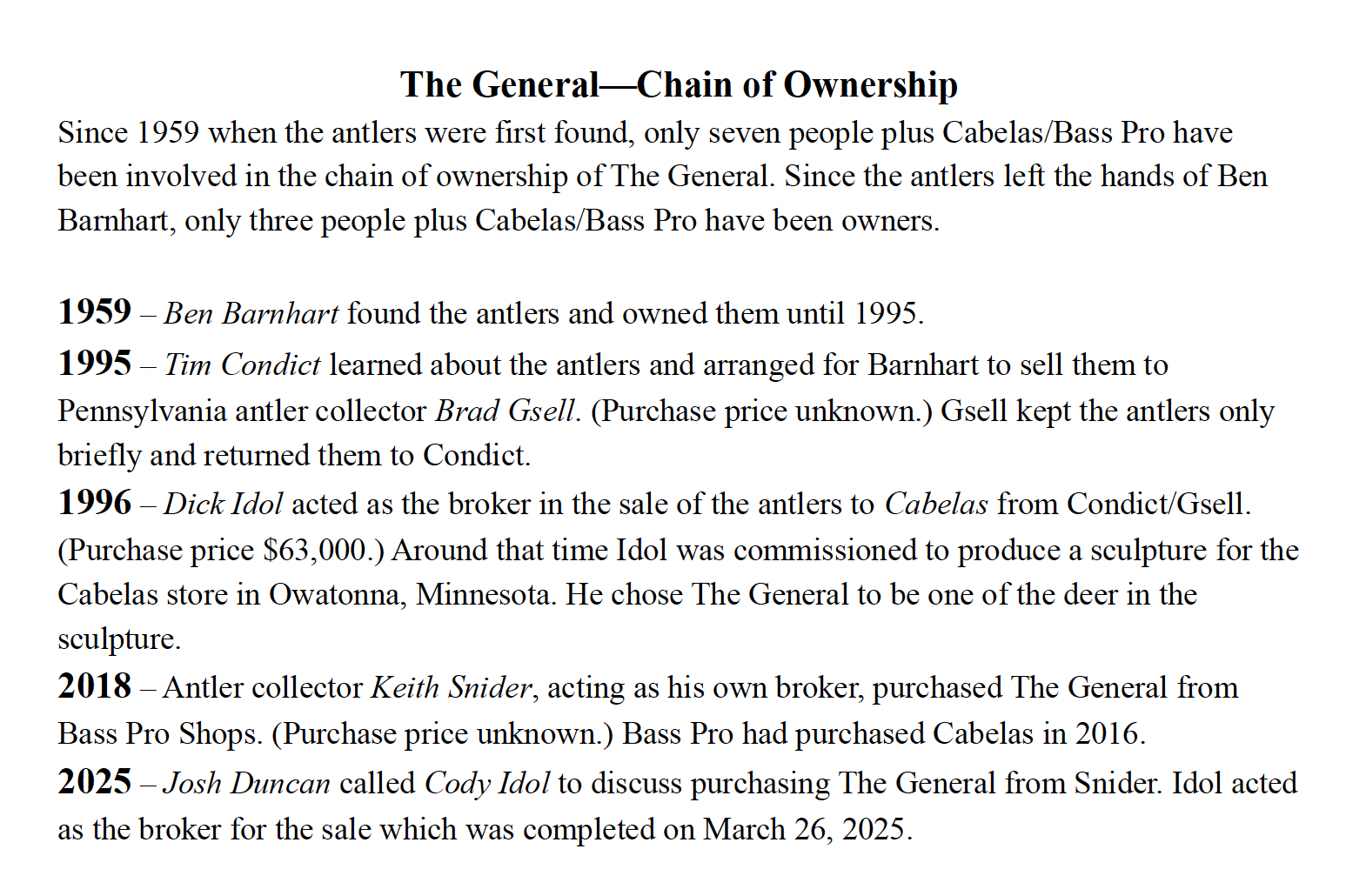

In 2025, West Virginia antler collector Josh Duncan decided to try to purchase The General and contacted Cody Idol to be the broker for the sale. Cody, a son of famed artist, sculptor, and whitetail enthusiast Dick Idol, is an expert in his own right. After negotiation, Keith Snider (who had purchased them from Bass Pro Shops in 2018) agreed to sell the antlers to Duncan. On March 26, 2025, the two parties signed a contract for $1 million. That’s a big price to pay out-of-pocket, but the two men agreed to installments and Duncan became the new owner.

Hunters will understand Duncan’s love of antlers because, like many of us, Duncan read about The General many years ago. He intended the purchase “as an investment in something that is way cooler than a stock or a bond, but like other investments it’s a stored value for my family.” Duncan said, “People will buy art and won’t think twice about it, but God made these antlers so they’re basically God’s art.”

Then the bad news started, and none of it would have happened without Duncan’s purchase because it led to social media interest, which led Barnhart’s neighbor Bill Saner to post photos given to him by Barnhart himself. Those photos revealed two additional points on the antlers. If Duncan had not purchased the antlers, they probably would have gone back to Bass Pro Shops, the snapshots would never have been revealed, and the truth would never have come out.

Forty days after Duncan’s purchase of lifetime, everything changed. The whitetail world’s big, bad, breaking news was that The General is not quite what anyone thought it was. Sometime after March 1995 and before the antlers were featured in a December 1996 North American Whitetail magazine article by Dick Idol, two small points had been removed from the right G-2 tine and the left G-3 tine — leaving no visible evidence.

Who did it? And why? It seems clear that the points were on the antlers the entire time Barnhart had them, evidenced by family photographs taken in the Barnhart farmhouse dated March 29, 1995 (37 years after Barnhart found the antlers and shortly before he sold them to a collector). The Barnhart images were posted to Facebook on May 5. Mike Charowhas, known as “The Antler Collector” saw them and told Duncan. Charowhas and Duncan notified Shane Indrebo, a co-owner of the North American Shed Hunters Club (NASHC), which had registered The General as its world record set of shed antlers.

A few days later, Duncan received a text message from Indrebo, indicating the news of the removed sticker points meant, regrettably, that The General’s antlers would no longer be recognized as the top white-tailed deer sheds. The club does not have an online listing of its records and the NASHC record book is not published at regular intervals. Currently, the club has no specific timetable, but Indrebo expects the latest edition to be published in 2026.

Of course, amidst all the questions, one major one was what to do about the million-dollar contract. Duncan and Snider wanted to maintain a lifelong friendship over their rare common bond of owning The General. After a long and deep conversation about it, and even though The General was no longer the bona fide world record shed antlers, Duncan decided he would not seek to void the contract. He wanted to give The General a future under his ownership.

Who shaved the points?

The chain of ownership isn’t long, and the window of time during which the points were removed is very short. In the early 1990s Tim Condict, an Oklahoma whitetail outfitter, was looking for property to lease for deer hunting in central Nebraska. He asked locals if they knew of any big antlers, and someone pointed him to the Barnhart farmhouse. After seeing the antlers, he convinced Barnhart they were worth selling.

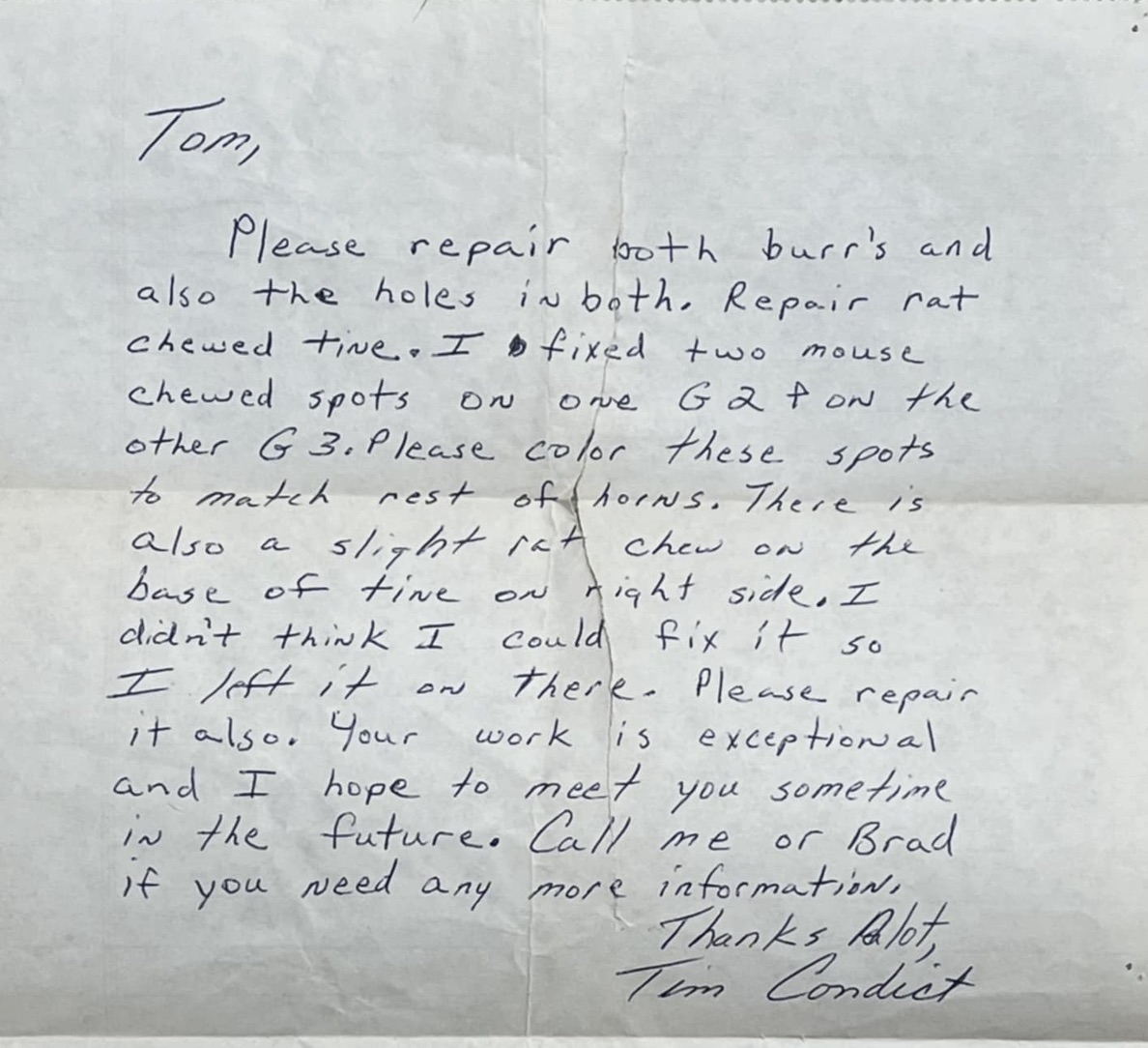

Before selling them, the Barnhart family took snapshots to preserve the memory of the antlers in the family and on the property where they were found. When Barnhart let the antlers go, they still had the two non-typical points. Condict acted as a broker to convey them to Brad Gsell, an antler collector in Pennsylvania. Before delivering them to Gsell, Condict sent them to a renowned antler repair specialist Tom Sexton in Iowa.

The undated letter from Condict describes the work he was asking Sexton to do. First, the burrs on both antlers needed repair because the back edges had been trimmed to fit them to the board they had been mounted on. Then, Condict said he “fixed two mouse chewed spots on one G2 + [plus] on the other G3.” He also asked Sexton to color-match the repairs and concluded with, “Call me or Brad [Gsell] if you need any more information.” The mention of Brad puts the letter on the ownership timeline of mid-1995 to early 1996. For unknown reasons, Gsell soon returned them to Condict.

Rodent damage during the long years the antlers were lying on the dirt barn floor isn’t surprising, but two areas described as “mouse chewed” seem to be the precise locations where (to be learned later) the antler points had been removed. Sexton’s excellent work was faithful to Condict’s request — he smoothed and polished the right G2 and the left G3 making them appear as though no damage or alteration of any kind had ever been there. His perfect repairs went undetected until May 5, 2025, when the Barnhart photos were revealed.

In the chain of ownership, we can be sure that no one at Cabelas, and not Dick Idol (who brokered them from Condict to Cabelas), Keith Snider, Cody Idol, or Josh Duncan (nor the many antler experts who had seen them through the years) had any idea the antlers had been altered.

Stay tuned for Part 2 as this story continues …